In Hot Pursuit of Morphea

A Rare Disease Gets the Full Treatment

April 2022

Morphea—or localized scleroderma—is a rare and potentially devastating autoimmune condition, with distinct subgroups, that causes inflammation and sclerosis of the skin and underlying soft tissue. It affects both children and adults, with an estimated incidence of 0.4–2.7 per 100,000 people.

Periods of activity—inflammation mingled with fibrosis—ultimately result in permanent tissue loss and pigment change. When this activity remains unchecked, it can produce permanent life-altering cosmetic and functional sequelae that include hair loss, atrophy (cutaneous, soft tissue, and bone), joint contractures, and—in children—growth restriction of the affected body site.

Crucial to limiting this damage is the early identification of activity and initiation of appropriate treatment, both of which morphea expert Heidi T. Jacobe, MD, MSCS, has found to be significantly inadequate. This lack was even more pervasive when she first began studying morphea in the later 2000s.

Crucial to limiting Morphea’s damage is the early identification of activity and initiation of appropriate treatment

When Dr. Jacobe unexpectedly encountered her first morphea patients in the mid-aughts, she knew little about this disease. As she began to recognize its profound impact on patients’ lives and how minimal and nebulous existing knowledge and treatment were, she realized that this was her path. Ever since, she has been dedicated to the research that enables the medical community to recognize and understand this disease and its subtypes, treat it appropriately, and open the way to developing more effective therapies.

Clinical and MRI findings with suspected deep morphea. Top: Scan (red box on thigh shows location) shows significant and subclinical subcutaneous involvement. Bottom: Scan (red box shows location) shows fascial involvement, which can be difficult to determine solely on clinical examination. (Reprinted with permission from LF Abbas et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:590–92.)

Patient Registry Advances Research in Morphea

Once Dr. Jacobe planned to devote herself to documenting and understanding the realities of this rare disease, she knew that first she had to establish a large and representative patient registry to guarantee accurate, meaningful results. It had to include varied disease severity, subtypes, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Beginning in July 2007, patients were recruited from within the UTSWMC system (encompassing two dedicated pediatric care facilities, a county hospital, and a faculty-based practice), and routinely enrolled through regional and national referrals from dermatologists and rheumatologists.

The Morphea in Adults and Children (MAC) cohort—which enables a database and a biorepository that holds samples of each patient’s sera, DNA, and immune cells—initially contained a total of 264 adults (≥ 18 years at enrollment) and children (≤ 17 years at enrollment).

Since its inception, MAC has grown to more than 900 participants: 60% adults, 40% children. Data are abstracted using a comprehensive clinical report form to provide information on demographics, clinical features, medical history, and family history. Each patient is examined by Dr. Jacobe, who assigns a clinical subtype based on Laxer and Zulian’s Padua criteria. Blood samples are obtained for immunologic and immunogenetic studies.

“I am very thankful to the patients who have been so generous with their time—and literally their blood, sweat, and tears—to help the cohort happen. The value is enormous,” Dr. Jacobe enthuses. And their generosity continues. “When I am embarking on a new study,” she adds, “we often contact the original cohort participants and invite them to participate. And they are amazingly helpful.”

“The other exceptional aspect is that some of my best research ideas actually come directly from people in the MAC cohort,” Dr. Jacobe says. “When we see these patients, they ask amazing questions and share very valuable insights. Because our goal is to improve their lives, it makes sense to study the questions that are important to them. For example, older children and teens and their parents asking me what they can expect as an adult drove the series of papers on adults with pediatric-onset morphea. Patients asking me if other people with morphea ever feel like their skin is on fire drove the studies on itch, pain, and QOL. Figuring out how we can scientifically and rigorously answer the questions that are important to patients has guided me throughout.”

Tying Subtypes to Reality

Because morphea is a heterogeneous disease, providing the best available care for patients and making meaningful progress in research both depend on the ability to classify patients accurately. Yet the fact that morphea is such a rare disease has been a serious impediment to developing accurate sub-type classifications.

Dr. Jacobe points out that current characterizations are based largely on expert opinion rather than prospective, systematic research. The few existing studies have not been sufficiently powered to provide in-depth analysis of the relevant clinical features of subtypes across the life span, they are predominantly retrospective, include only adult or pediatric patients, and are typically focused exclusively on rheumatology or dermatology.

“As a result,” Dr. Jacobe says, “the demographic and clinical features of morphea, particularly of the less-frequent subtypes, had remained poorly characterized. And little has been known about the differences between adults and children with this disease.”

The MAC cohort enabled Dr. Jacobe to begin correcting this deficit, revising these subtypes to make them accurate and useful and developing an effective algorithm for evaluating patients.

Click on the image below to enlarge the chart.

Dr. Jacobe’s algorithm for the evaluation of patients with morphea. ROM: range of motion; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; U/S: ultrasound; PT: physical therapy; OT: occupational therapy. *Presence of seizures, hemiparesis, or other localizing neurologic deficits is an indication for emergency care. (Copyright 2021 UpToDate, Inc. and its affiliates and/or licensors. All rights reserved.)

Pansclerotic. Dr. Jacobe’s first target was the pansclerotic subtype because it showed the greatest descriptive variation between the different classification systems. Using patients from the MAC cohort, she identified its prevalence and then described its demographic and clinical features compared to generalized morphea.

She found that patients in this subtype have a shorter time to diagnosis; are much more likely to be male (46.25% vs 6%); have substantially higher rates of functional impairment (61.5% vs 16%) and deep involvement (61.5% vs 17%); and score significantly higher on several assessment instruments (the Rodnan Skin Score, Localized Scleroderma Skin Damage Index, and Physician Global Assessment of Disease Damage).

Dr. Jacobe and her colleagues concluded that the pansclerotic subtype is a distinct clinical phenotype with a more rapidly progressive and severe course commonly accompanied by disability. Its presence “should alert practitioners to the possibility of significant morbidity and thus the need for early aggressive treatment.”

Generalized. Next, Dr. Jacobe found her way around the barrier to classifying generalized morphea. Because it lacks cohesive clinical features, it was typically classified simply by the presence of 4 or more lesions larger than 3 cm in diameter in at least 2 of 7 anatomical sites. Jacobe hoped to replace that with computerized lesion mapping for objectively subtyping these patients. She and her coworkers formed two groups from previously diagnosed MAC cohort patients who had clinical photographs of sufficient quality for lesion mapping. They created their initial maps with the discovery cohort, then put mapping to the test in the validation cohort.

Mapping produced two consistent lesion distribution patterns—isomorphic and symmetric—together encompassing most of each cohort. The isomorphic subset involved areas of chronic skin friction (waistband and brassiere-band); the symmetric subset involved lesions symmetrically distributed on the trunk and/or extremities.

In addition, these two discrete patterns reflected unique demographic and clinical features. The isomorphic group was older (55.6 vs 42.2 years), all female (30/30 vs 38/43), and more often had lichen sclerosus changes (12/43 vs 8/43). In the symmetric subset, involvement of the reticular dermis, subcutaneous fat, and/or fascia were more common (10/43 vs 1/30). “Because they clearly possess distinctive demographic and clinical features,” Dr. Jacobe notes, “these two subsets more accurately define the phenotype of generalized morphea.” And she recommends revising classification.

Linear. Dr. Jacobe has also provided essential data for linear morphea, the predominant subtype in children and the one most frequently associated with musculoskeletal, cosmetic, and neurologic irregularities. Previous studies suffered from a variety of limitations. They were typically limited to pediatric onset, lacked systematic comparisons with other morphea subtypes, and were plagued with procedural issues that included inconsistent standards due to using multiple examiners from numerous sites.

The MAC cohort allowed Dr. Jacobe and her coworkers to be thorough and accurate, comparing linear morphea patients—196 with pediatric onset, 95 with adult onset—with other subtypes, and then prospectively examining them for 3 years to determine changes in clinical scores and quality of life (QOL).

An important discovery was that the life-altering impact of functional limitations experienced by one-third of these patients is not captured by existing dermatology-based QOL measures (which Dr. Jacobe is currently addressing). Dr. Jacobe advises practitioners to evaluate for functional impairment, particularly if deep involvement is present. She underlines the high frequency of adult-onset linear morphea, its association with the same functional limitations as in pediatric onset, and the efficacy of current standard-of-care treatments to abrogate disease activity and stabilize permanent damage in both age groups. It is critical to identify patients with active, inflammatory morphea and promptly initiate appropriate treatment.

Mucocutaneous. Dr. Jacobe recently provided demographic and clinical data for patients with mucocutaneous findings (both genital and oral lesions), a very poorly studied group. Although the overall frequency of oral lesions is low— only 2.4% in the MAC cohort overall—they predominated in younger patients with facial linear morphea and affected almost all (94.4%) of those with deep involvement.

Mucotaneous morphea with oral involvement. Oral morphea lesions cause reduced oral aperture (left), asymmetry of jaw and mouth (center), and asymmetric extension of tongue (right). (Reprinted with permission from S Prasad et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:114–20.)

Genital lesions are also infrequent overall (3.7% of the cohort) but represent 12.2% of all female patients with generalized morphea, specifically among postmenopausal women with overlying extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Dr. Jacobe advises practitioners that “patients at high risk for developing mucocutaneous morphea should be identified and treated promptly.”

Classification Systems. Most recently, Dr. Jacobe assessed the three commonly used morphea classification systems, which only partially overlap: the Padua criteria, the Peterson criteria, and the system developed by the European Dermatology Forum (see Table 1, page 5). None had yet been systematically evaluated to determine their ability to categorize patients into demographically and clinically coherent groups. The unavoidable result has been confusion among practitioners and investigators, impairing both patient care and research.

To pin down the actual capability of each of these three systems, Dr. Jacobe and her team expanded their patient population for this analysis. In addition to the MAC cohort, they included the 16-year-old National Registry for Childhood-Onset Scleroderma at the University of Pittsburgh, headed by Cassie Torok, MD, a pediatric rheumatologist who collaborates with Dr. Jacobe. Their cross-sectional study asked: How frequently does each system successfully categorize patients with clinically relevant morphea subtypes? The Padua criteria dramatically outperformed the other two, successfully classifying 95% of patients, although Jacobe points out that some ambiguities remain to be resolved. The Peterson criteria correctly categorized only 56% of these patients, and the European Dermatology Forum classification system—the most recent entry—was successful just 52% of the time.

Table 1. Performance of morphea subtype classification schemes in categorizing patients

| Morphea subtype |

|---|

| Mayo Clinic (Peterson et al.) criteria (533 of 944 patients [56%] categorized) |

| Morphea |

| Plaque |

| Generalized |

| Bullous |

| Linear |

| Deep |

| Padua criteria (900 of 944 patients [95%] categorized) |

| Circumscribed morphea |

| Linear morphea |

| Generalized morphea |

| Pansclerotic morphea |

| Mixed morphea |

| European Dermatology Forum criteria (487 of 944 patients [52%] categorized) |

| Limited |

| Morphea |

| Plaque |

| Guttate |

| Superficial |

| Generalized |

| Linear |

| Deep |

| Mixed |

Assessing the Damage

Ultrasound (U/S). Good outcome measures are required for determining whether a therapy is effective, both in routine clinical practice and in clinical trials. When Dr. Jacobe began to treat morphea patients, the commonly used outcome measure in disorders of skin thickening was a subjective score based on palpated skin thickening, an approach “fraught with error,” Dr. Jacobe points out. She was convinced that U/S measurements—noninvasive, quantitative, valid, reproducible, and responsive to change—held great promise. Dermatologic U/S had been introduced in Europe and Japan, and in Europe, 20–25 MHz U/S had already become the best- established outcome measure in morphea and scleroderma.

Although U/S in the United States had a long history in medicine for imaging the body, it was only just beginning to receive attention in dermatology. Dr. Jacobe began working with the 10–15 MHz equipment available in the U.S. and found it to be excellent. Preliminary studies in the U.S. on this lower-frequency ultrasonography eventually demonstrated similar attributes to those found for 20–25 MHz. Then Dr. Jacobe worked with a small group of patients from the MAC cohort to correlate U/S findings with lesion stage (inflammatory, sclerotic, or atrophic), clinical scoring system, and histologic traits.

For each patient, a single lesion site and a control site were examined with U/S, then biopsied. Each lesion was assessed for subtype and clinical stage, and assigned a Modified Rodnan Skin Score (mRSS) for skin thickness. The results reflected extremely high validity and reliability, clearly demonstrating the capabilities of U/S in assessing morphea patients. It differentiated between all clinical stages of the disease. It could differentiate active disease—which appeared hyperechoic (sclerosis) or isoechoic (inflammation)—from atrophy or damage (which appeared hypoechoic).

Dr. Jacobe and her team also found that U/S demonstrated a significant correlation between the amount of sclerosis on histologic examination—the gold standard—and the degree of echogenicity. Jacobe concluded at the time that this level of performance identifies 14-MHz ultra- sonography as a useful outcome measure. She also speculated that its depth of penetration may be a useful tool to investigate the depth of involvement beyond the dermis

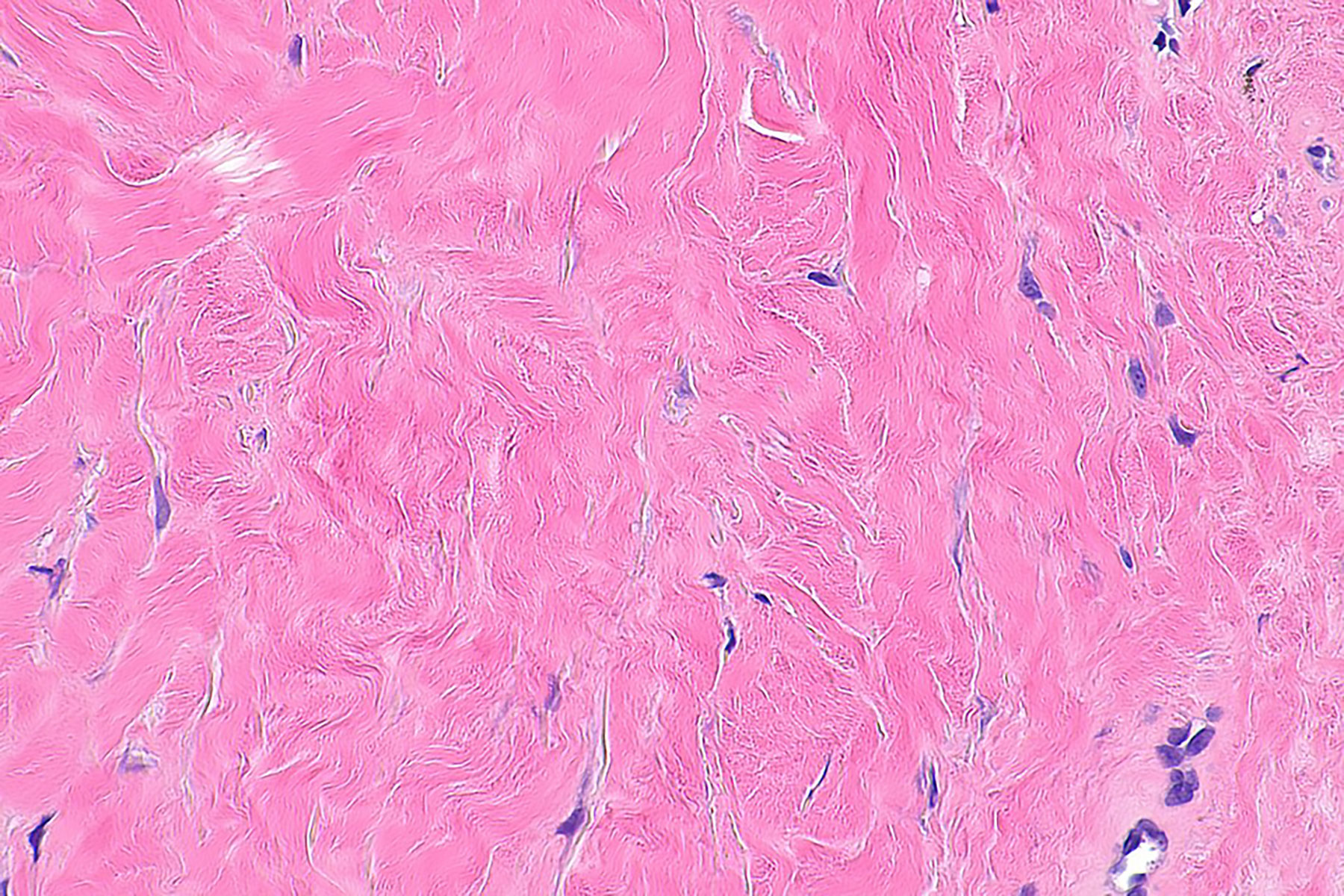

Histopathology. To answer the need for a clear picture of the relationship between histopathological features and their clinical correlates, Dr. Jacobe and her team carried out a cross-sectional study of 83 patients in the MAC cohort. The histological features involved microanatomical location and degree of sclerosis and inflammation, and these were correlated with patient-reported symptoms and physician-based measures of severity.

The results showed sclerosis pattern to be associated with morphea subtype, the presence of patient-reported symptoms, and functional limitation. Pain and tightness were associated with a bottom-heavy pattern of sclerosis, but not a top-heavy pattern. Dr. Jacobe pointed to the benefits for patient care, advising that “histopathological examination of morphea can assist in identifying patients who may require additional monitoring and treatment.” In line with this, she adds that “features such as patterns of sclerosis and severity of inflammation should routinely be included in pathology reports to help aid in clinical management.”

Histopathological changes. In top-heavy morphea (left), sclerosis is moderate to severe in the papillary and superficial reticular dermis, with the mid- and reticular dermis relatively spared. In bottom-heavy morphea (right), sclerosis is moderate to severe in the mid- and reticular dermis, relatively sparing the superficial and papillary dermis. (Reprinted with permission from D Walker et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:1124–30.)

MRI. More recently, Jacobe has looked at the potential value of MRI assessment for accurately assessing disease depth, extent, and inflammatory activity. They are all critical for management, but often difficult to discern on clinical examination alone.

Dr. Jacobe’s study focused on deep morphea, comparing clinical assessment with MRI findings. She hypothesized that MRI would be a useful clinical adjunct through its ability to demonstrate subclinical morphea activity and expansion. In a cross-sectional analysis of 20 consecutive patients from the MAC cohort with suspected deep morphea, MRI findings confirmed clinical suspicion of soft tissue involvement in 26 of 27 scans, and 7 scans showed involvement of muscle and/or deep fascia.

Clinically active disease was suspected in 15 of these patients, but MRI results demonstrated it in 17. In 5 patients, MRI findings showed disease activity when none had been apparent clinically. (The validated clinical parameters used to determine activity as part of the mLoSSI score did not correspond to features of activity on MRI findings.) In addition, MRI results showed lesions extending beyond clinical margins by a mean of 6.3 cm, indicating that pathology routinely exceeds clinical detection.

These significant discrepancies between clinical and MRI evaluation of the extent of disease highlight the risk of misclassifying lesions as inactive when using the mLoSSI aslone. This risk increases steeply in deep morphea, in which activity is difficult to detect. The presence of clinically unsuspected activity on MRI changes management, with continuation or escalation of treatment and subsequent control of activity.

Pathology

Role of Skin Trauma. The development of lesions at sites of skin trauma occurs in numerous dermatologic conditions. Several case reports in the morphea-related literature intrigued Dr.Jacobe, as they noted precipitating events including friction from clothing, injection, herpes zoster infection, and radiation therapy. Dr. Jacobe did a cross-sectional assessment of the MAC cohort—with 329 patients registered at that time—for skin lesions distributed in areas of prior (isotopic) or ongoing (isomorphic) skin trauma. She found that 16% had developed initial morphea lesions at sites of skin trauma.

Patients with an isotopic distribution had greater clinical severity (mean modified Rodnan Skin Score of 13.8 vs 5.3) and greater impact on life quality (mean Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] score 8.4 vs 4.1) than those with an isomorphic distribution. The most common traumas were surgery (isotopic) and chronic friction (isomorphic). These results emphasize the importance of avoiding elective procedures and excessive skin trauma or friction in these patients. They also support hypotheses on the role of aberrant wound healing and stress in the development of fibrosis, and thus provide insight into the pathogenesis of morphea in this patient cohort.

HLA Class I and II. Data from a variety of sources increasingly suggested that morphea is immunologically mediated. Dr. Jacobe had contributed to this with an analysis of MAC cohort patients that found a high prevalence of concomitant and familial autoimmune disease, systemic manifestations, and antinuclear antibody positivity in the generalized and possibly the mixed subtypes, which also suggested that they are systemic autoimmune syndromes and not skin-only phenomena.

Then Dr. Jacobe provided critical evidence with a nested case-control study of MAC cohort patients that identified the HLA class I and class II MHC alleles—which are responsible for fine-tuning the adaptive immune system—associated with morphea. They are also different from those found in scleroderma—the first clear evidence that morphea is immunogenetically distinct.

These particular HLA alleles are, however, associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and other autoimmune conditions, and population-based studies indicate that RA brings an increased risk of morphea. This may point to a common susceptibility allele.

Disease Biomarker. In a more pragmatic context, Dr. Jacobe hoped to find a biomarker of disease. “Because the goal of therapy is to shut down active disease to abrogate permanent sequelae, the ability to assess disease activity is crucial to management. And though some morphea patients present with clearly active and severe disease,” she adds, “many present with lesions in evolution. In those cases, the degree of activity is uncertain and the potential for extension of lesions is unknown.”

Yet until Dr. Jacobe’s successful search for a disease biomarker, practitioners had only clinical examination and musculoskeletal imaging to rely on. Numerous cytokine possibilities had been reported in the sera of patients with morphea, but few had been systematically studied in a large patient cohort or looked at in association with validated measures of disease activity.

Until Dr. Jacobe’s successful search for a disease biomarker, practitioners had only clinical examination and musculoskeletal imaging to rely on

Dr. Jacobe was particularly impressed with the evidence pointing to IFN-regulated pathways and undertook a three-part study of MAC cohort participants to explore this. A case-control study to identify dysregulated cytokines and chemokines in patients used multiplexed immunoassays and transcriptional profiling of serum and whole blood, respectively. A longitudinal study looked at serum concentrations of these cytokines during active and inactive disease.

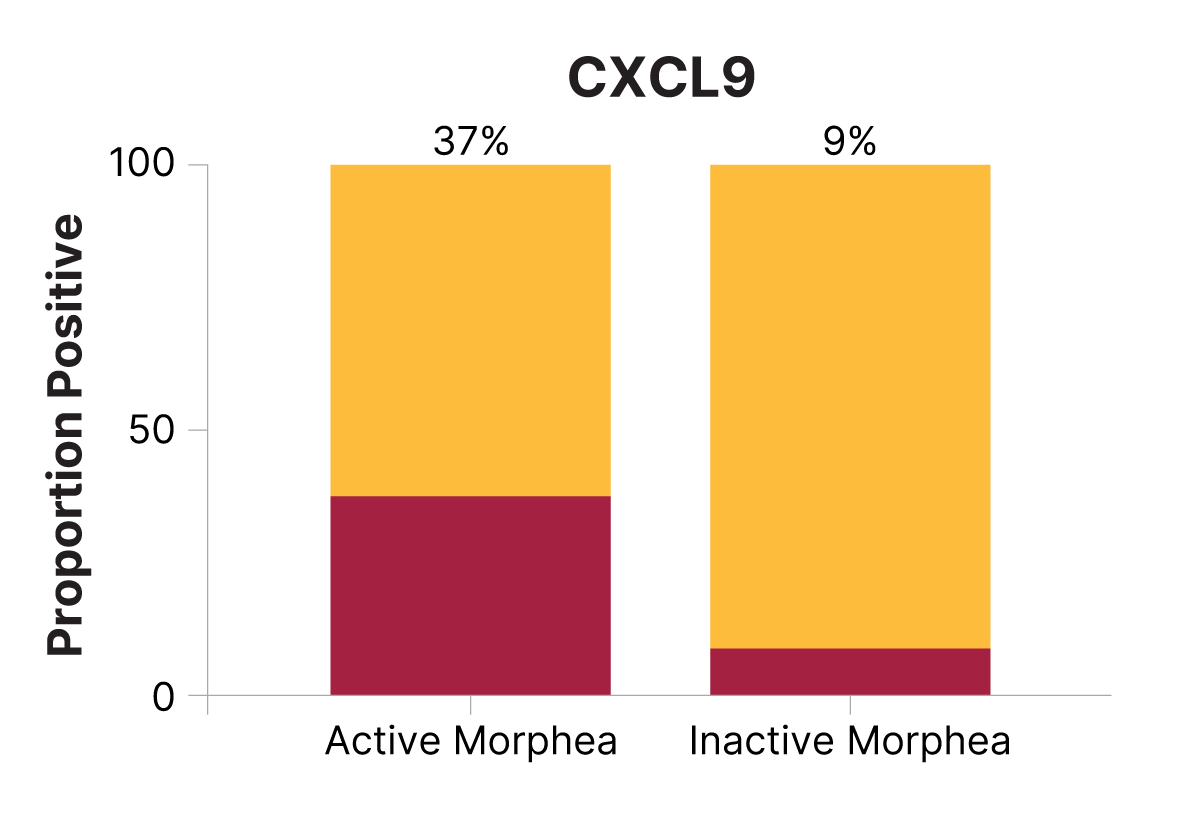

The final component determined the cellular source of these cytokines. Transcriptional and cytokine profiles identified the inflammatory small cytokine CXCL9—induced by IFNγ—as a biomarker of disease activity. CXCL9 is part of a chemokine superfamily that encodes secreted proteins involved in immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes, and is thought to be involved in T-cell trafficking. CXCL9 showed high frequency in 37% of patients with active morphea (see bar graph, page 7), while the low frequency among those with inactive disease (9%) was very similar to that in control subjects (4%). CXCL9 also showed a high correlation with clinical disease activity (r= 0.44, P= 0.0001).

CXCL9 is increased in active morphea, decreases in inactive disease. (Reprinted with permission from JC O’Brien et al. J Invest Dermatol. 2017;137:1663–70.)

The clear involvement of IFNγ is strong evidence for the dominance of Th1 T-cells in morphea, which holds implications in the search for more-effective treatments. (As a side note, the chemokine CXCL10 also showed a significant presence in the patient group, but as a marker of overall disease severity regardless of active or inactive disease.) The absence of a transcriptional IFN signature in patients’ peripheral blood led Dr. Jacobe and her colleagues to hypothesize that morphea may result from skin-directed immune dysregulation rather than a systemic one as in systemic sclerosis. These results are now awaiting confirmatory study.

Treatment

Dr. Jacobe recognized from the outset that little was known about diagnosing, evaluating, and treating morphea. This heightens the likelihood of delays in both diagnosis and initiation of therapy, which negatively affects patient care. And this gap in knowledge hinders planning for clinical trials and therapeutic guidelines.

Dr. Jacobe took the first steps in filling in these blanks, using the MAC cohort. She found that 63% of the cohort patients had received their diagnosis more than 6 months after the onset of symptoms. The majority of patients (83.5%) saw a dermatologist. Those seeing a rheumatologist tended to have the more severe forms of morphea (linear and generalized). The most prescribed treatment was topical corticosteroids (63%).

Dermatologists predominantly prescribed topical treatments or phototherapy, even to patients with severe disease. Rheumatologists, on the other hand, predominantly prescribed systemic immunosuppressives and physical therapy. Thus, therapeutic decision-making was largely determined by the provider’s specialty rather than disease characteristics, and Jacobe also found that “many treatments with little or no proven efficacy were frequently used, while others with proven efficacy were underused.”

Along with documenting this situation in practice, Dr. Jacobe also carried out a thorough and systematic literature review of morphea treatments to identify those with the most evidence for efficacy, and those with no support. Overall, treatment works best in inflammatory disease, “and thus therapy should be initiated as early as possible,” Dr. Jacobe emphasizes.

Severity, progression, and depth should also play a role in therapeutic decision-making. She and a colleague found that phototherapy and methotrexate had the greatest evidence for efficacy. They suggested that narrowband UVB is appropriate for progressive or widespread superficial dermal lesions; broadband UVA/UVA-1 is appropriate for widespread or progressive deeper dermal lesions.

Systemic treatment with methotrexate, corticosteroids, or both is indicated for deep or function-impairing lesions and rapidly progressive or severe widespread disease. Topical treatment with calcipotriene or tacrolimus is supported for limited, superficial, inflammatory lesions. There was no support for the use of oral calcipotriol, D-penicillamine, IFNγ, or antimalarials.

“Overall, treatment works best in inflammatory disease and (thus) therapy should be initiated as early as possible.”

In a later survey of practitioners that differentiated between dermatologists and rheumatologists treating adult and pediatric patients, Dr. Jacobe learned that the treatment differences she had identified earlier—the dermatologists’ preference for topicals and the rheumatologists’ preference for systemic immunosuppressives—were minimized among pediatric providers. Both groups reported greater use of systemic immunosuppressives in moderate to severe morphea subtypes, and Dr. Jacobe suspected that pediatric providers may adhere more closely to published treatment plans because of their greater awareness of morphea.

“These results underscore the need for comparative studies for better treatment evidence, and multidisciplinary input for generalizability,” Dr. Jacobe had concluded. And she has contributed in this way as well.

“These results underscore the need for comparative studies for better treatment evidence, and multidisciplinary input for generalizability”

UVA1 Phototherapy. In the mid-aughts, Dr. Jacobe knew that UVA1 (340–400 nm)—emerging in Europe as a specific UVR phototherapeutic mechanism—had been shown to be an important treatment option for many debilitating skin conditions that included several sclerosing conditions and other dermatitides. In many cases it was more effective than other phototherapy modalities. Its ability to penetrate the deep layers of the skin enable it to affect disease-causing T-cells, and to activate endothelial cells to promote neovascularization. It was relatively free of side effects associated with other phototherapy regimens, including erythema and cellular transformation.

An early study in the United States—a retrospective analysis of 92 patients from 4 medical centers, including UTSWMC—involved a range of cutaneous diseases. Dr. Jacobe reports that two-thirds of them—including patients with morphea—showed a fair-to-good response (26–100% improvement). Dr. Jacobe’s next step was assessing the effectiveness of UVA1 phototherapy in darker skin. Most reports evaluating the benefits of UVA1 phototherapy had been from Europe and thus focused on a predominantly Caucasian population.

Yet despite this paucity of data on darker skin types, it was widely assumed that increased pigmentation was a barrier to effective UVA1 photo therapy. To determine the reality, Dr. Jacobe carried out a retrospective analysis of 101 patients—including 47 with morphea and 34 with scleroderma—who had been treated at UTSWMC’s phototherapy center. She compared efficacy among Fitzpatrick skin types using clinical improvement scores based on body surface area, erythema, induration, sclerosis, pigmentation, and symptoms of pain or pruritus. Dr. Jacobe found the common assumption to be wrong.

Improvement scores and mean cumulative UVA1 doses were not significantly different among the Fitzpatrick skin types—and thus there was no correlation between improvement score and skin type. “UVA1 should be considered as a therapeutic option in more-darkly pigmented patients,” Dr. Jacobe says.

Clinical improvement score by skin type in morphea patients treated with UVA1. Mean ±SD. (Reprinted with permission from HT Jacobe et al. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:691–96.)

“UVA1 should be considered as a therapeutic option in more-darkly pigmented patients”

As positive experience with UVA1 phototherapy for treating morphea expanded, Dr. Jacobe wanted to look at the risk of recurrence after successful treatment and identify any variables that could warn of a possible recurrence. By now she had the MAC cohort to work with and was able to do a case series and prospective cohort study. She found that 60% of the patients treated with UV1 had responded (n= 37), a rate supporting it as an acceptable therapeutic option for patients who are not candidates for systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Of these 37 patients, 46% overall eventually experienced recurrence of active morphea lesions. Timed from the final treatment, 2-year and 3-year recurrence rates were 44.5% and 48.4%. Recurrence risk was the same for adults and children, for all morphea subtypes, for all skin types, for medium- and high-dose regimens.

The single variable associated with recurrence was the duration of disease prior to UVA1 treatment. “This indicates that treatment doses in the medium-high UVA1 range are adequate,” Dr. Jacobe says, “and it also tells us about that patient with long-standing morphea may benefit from frequent follow-up and maintenance therapy.”

Mycophenolate Mofetil/Mycophenolic Acid. First-line systemic therapy for morphea includes methotrexate with or without systemic corticosteroids. When this is ineffective, not tolerated, or contraindicated, a trial of mycophenolate mofetil or mycophenolic acid (referred to here as mycophenolate), is recommended. Because the evidence supporting this was based on very few patients, Dr. Jacobe added to the data with a retrospective cohort study of 77 mycophenolate-treated patients, gathered from 8 institutions, with predominantly severe recalcitrant disease.

When Dr. Jacobe examined efficacy and tolerability at 3–6 and 9–12 months of treatment, results supported mycophenolate’s use as a well-tolerated and beneficial treatment for recalcitrant severe disease. After 9–12 months of treatment, disease was either improved or stable in 87% of these patients. The most common adverse effects were gastrointestinal (31%), cytopenia (4%), and infection (3%), with 12 patients ultimately discontinuing because of adverse effects.

Table 2. Disease response to treatment with mycophenolate

| Disease response | Patients, No./Total No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment with mycophenolate | Addition of mycophenolate | All | |

| At 3–6 mo | |||

| Progressive disease | 1/11 (9) | 6/62 (10) | 7/73 (10) |

| Stable disease | 2/11 (18) | 20/62 (32) | 22/73 (30) |

| Improved disease | 8/11 (73) | 36/62 (58) | 44/73 (60) |

| Beneficial response* | 10/11 (91) | 56/62 (90) | 66/73 (90) |

| At 9–12 mo | |||

| Progressive disease | 0/8 (0) | 7/46 (15) | 7/54 (13) |

| Stable disease | 1/8 (13) | 13/46 (28) | 14/54 (26) |

| Improved disease | 7/8 (88) | 26/46 (57) | 33/54 (61) |

| Beneficial response | 8/8 (100) | 39/46 (85) | 47/54 (87) |

Pediatric Onset Morphea

Early on in her involvement with the spectrum of morphea patients, Dr. Jacobe confronted significant gaps in knowledge concerning pediatric morphea. The prevalence of morphea in childhood was not well established beyond reports suggesting that approximately two-thirds of linear morphea cases occur before age 18, and 20% to 30% of morphea cases overall begin in childhood. And although “studies had described substantial morbidity in children with morphea,” Dr. Jacobe adds, “none appeared to have addressed what happens after these patients turn 18 and enter adulthood.”

The MAC cohort had been in existence for 2 years at that point and held 200 patients. Dr. Jacobe and a colleague identified 27 adults with pediatric-onset morphea (APOM). At the time of study enrollment their mean age was 30.6 years (range: 18–78 years), and the mean age of morphea onset was 11.5 years (range: 3–17 years).

The large majority—74%—had linear morphea, 19% had generalized morphea, and 7% had plaque-type disease. Permanent sequelae were identified in 56%, all in linear morphea cases: limited range of motion, deep atrophy, limb-length discrepancy, and joint contracture. DLQI scores for 6 of the 27 patients indicated a moderate to very large effect on QOL, with limited range of motion playing a significant role. “In contrast to the results of prior studies, we found that 89% of our cohort had continued disease activity.”

Data underscored the progressive nature of morphea, as most of these 27 patients—including all of those with linear morphea—had developed new or expanded lesions over time. Results also suggested that APOMs develop autoimmune disorders in adulthood.

Despite the clear and continued severity of their disease as children and adults, Dr. Jacobe found that topical therapy predominates in this group. This points to significant under-treatment and the likelihood of detrimentally affecting long-term outcome. Dr. Jacobe addressed this. “Our data indicate the presence of a subset of patients with active disease in adulthood who need lifelong evaluation and repeated courses of aggressive treatment to prevent the substantial morbidity noted in our group. And parents of children with morphea need to be counseled on the possibility of recurrence, and on the need for vigilance in identifying and seeking treatment for new activity.”

“Parents of children with morphea need to be counseled on the possibility of recurrence, and on the need for vigilance in identifying and seeking treatment for new activity.”

When Dr. Jacobe approached this group again, it had become apparent that approximately 50% of adult patients have had their disease since childhood. And the MAC cohort had grown sufficiently to more than double the number of adults with pediatric-onset morphea, which now stood at 68. This time, they were compared with a group of adult-onset patients to compare both clinical outcomes and morphea’s impact on HRQOL (health-related QOL).

Dr. Jacobe learned that patients with pediatric-onset disease were less likely to have active disease, and that those who did have active disease had lower activity levels. However, the severity of their disease damage was higher than or equivalent to that of adult-onset disease.

When it came to HRQOL, patients with pediatric-onset morphea had significantly more-favorable scores. “This stands in contrast to studies of several other rheumatic conditions in adults with pediatric-onset disease, in which overall HRQOL was found to be negatively affected in at least some dimensions,” Dr. Jacobe notes.

“Results of this study have several implications for practice,” Dr. Jacobe points out. Reiterating their earlier study, the reality that many patients with pediatric-onset morphea will experience active disease into adulthood means that pediatric patients should have regular follow-up into adulthood and be counseled appropriately to self-monitor for disease reactivation.

Patients with adult onset may have increased disease severity, including impairment due to symptoms of their skin lesions. These aspects must be considered when deciding on optimal treatment.

Discovering Morphea

Dr. Jacobe’s dedication and formidable progress in illuminating morphea are the fruit of serendipity amplified by luck. In medical school she had particularly enjoyed the intersection between the immune system and the skin. Rheumatologic conditions were among the diseases that she found particularly intriguing, but she did not have a delineated goal.

Serendipity opened the door to morphea when Dr. Jacobe was hired at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UTSWMC). Her chair, Dr. Paul Bergstresser, offered her the responsibility for modernizing the department’s phototherapy unit and turning it into one of the region’s premier providers of phototherapy, and he provided a generous budget for accomplishing this.

“I was able to purchase a UVA1 phototherapy unit,” Dr. Jacobe says. “There were very few in the United States at that time, and the primary one was at the University of Michigan.” She visited that department to discuss their experience, which emphasized the promise they found for treating patients with sclerosing skin conditions.

Back at home, Dr. Jacobe initiated an advertising campaign announcing the department’s new phototherapy capabilities and noting that responsive conditions included sclerosing diseases—and morphea. “Morphea’s rare occurrence meant that few physicians were comfortable with it or had sufficient treatment knowledge, and we were an asset for them.” As a result, morphea patients began to appear among those referred for UVA phototherapy.

“In seeing patients living with morphea, I realized that I wanted to learn more about their experience,” Dr. Jacobe recalls, “but I quickly discovered there was very little available to read—and that no one was studying morphea. My patients were asking me about their morphea and their prognosis, and I could not answer them.” Dr. Jacobe was determined to change this but knew that she lacked the research training to do it effectively.

At that point, luck entered the picture. “Dr. Bergstresser, and then Dr. Kim Yancey, supported my research training.” Once this was completed, Dr. Jacobe established the patient registry known as the Morphea in Adults and Children (MAC) cohort—a database of close to 1,000 patients that has enabled her continuing exploration of a broad range of research questions.

Health-Related QOL for Adult Patients

After studies elsewhere had yielded conflicting results, Dr. Jacobe collected prospective data from 73 adult patients in the MAC cohort to identify a clear profile of the impact created by this disease. Her results included some surprises.

Multidimensional HRQOL scales measured impact. Skindex-29+3 assessed skin-specific HRQOL for the previous month with the emotions, symptoms, and functioning sub- scales. The Short Form (SF)-36 looked at aspects of general health. The skin-related DLQI was tied to the previous week. Patients also completed the SCQ (Self-administered Comorbidity Questionnaire). Pruritus and pain were assessed on a visual analogue scale. Patient data were correlated with physician-based outcomes measures, the clinical scores from the mRSS (modified Rodnan skin score) and the then-newly validated LoSCAT (Localized Scleroderma Cutaneous Assessment Tool).

Dr. Jacobe found conclusively that morphea impairs HRQOL in adults. Both increased severity of active disease and the presence of comorbid conditions were correlated with worse HRQOL. Patients with generalized disease showed worse scores compared to the other subtypes. “We confirmed prior observations that pain and itch—which itself was significantly correlated with lesion activity—especially were strongly associated with poor HRQOL,” Dr. Jacobe points out. “In fact, they were stronger correlates than the location of lesions in cosmetically or functionally sensitive sites.”

Both increased severity of active disease and the presence of comorbid conditions were correlated with worse HRQOL

Results demonstrated that morphea’s negative impact on HRQOL is similar to that occurring with disorders such as atopic dermatitis, rheumatoid arthritis, vitiligo, and alopecia, especially in the domains of emotions and mental health. The multiple ways in which intensity of symptoms correlates with diminished HRQOL “emphasizes the importance of addressing active lesions in clinical practice,” Dr. Jacobe underlines. Surprisingly, socioeconomic status was not associated with morphea’s impact on HRQOL despite the reality that these factors are known to have a strong effect. Dr. Jacobe suspects that their unsuccessful effort to recruit a diverse patient population was responsible for this apparent lack of correlation.

“A notable finding from our study,” Dr. Jacobe says, “is that participants had a high level of concern that morphea may affect their internal organs.” She strongly suspects that this reflects the ability of many patients to attempt researching their disease online, and the likelihood of encountering sources referring interchangeably to morphea, localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis, and scleroderma. The unfortunate result is significant confusion about their diagnosis and prognosis. “And this highlights the need for providers to educate their patients appropriately,” Dr. Jacobe stresses, “particularly with respect to differences between morphea and scleroderma.”

Summing up, Dr. Jacobe asserts that “morphea exerts a negative influence on HRQOL, particularly in the domain of emotions, and patients have significant concern about the systemic implications of their disease. With this now in mind,” she adds, “providers can be better equipped to recognize and address the components of morphea most worrisome to their patients.”

High Points

Looking back over her explorations of morphea so far, Dr. Jacobe refers to the transformative discovery that morphea’s active periods are driven by inflammation, which in turn ultimately drives the characteristic collagen production and leaves behind permanent changes. “When I began seeing morphea patients,” she recalls, “it was thought to be a disease of collagen, and thus not responsive to treatment. For me, one of the most exciting and satisfying things has been to be part of the larger understanding that morphea is really a disease of inflammation—and thus responsive to therapy when caught early.”

“Morphea is really a disease of inflammation—and thus responsive to therapy when caught early”

The second substantial source of satisfaction for me has been the rare ability to study patients of all ages, and especially to follow pediatric patients into adulthood. Typically, children are seen by pediatric dermatologists or rheumatologists, and then passed on once they reach age 18.”

Current Directions

Dr. Jacobe is collaborating very closely with Dr. Torok in Pittsburgh, using single-cell RNA sequencing to identify the gene expression portrait in active disease and then which of those genes become inactive after successful treatment.

She and Dr. Torok are also following the evolution of these active-disease gene expression signatures over time in both children and adults.

They are using animal models to make sure that their sequencing observations are biologically important. “Then once we know which genes are turned off with successful treatment, we can ask if there are drugs in development, or candidates for repurposing, that could be effective here,” Dr. Jacobe explains. “At this point the only proven treatments for morphea are older drugs—methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil—with a more substantial side effects profile. But now we have a spectrum of newer agents that are much more targeted and less toxic, and we are hoping to develop the tools for making intelligent treatment choices.”

Thinking ahead to evaluating new therapy targets and treatments, it will be essential to have valid and meaningful outcome measures. Dr. Jacobe reports that she and her coworkers “have been working very hard on validating a clinical score for morphea, and on validating a morphea-specific patient-reported outcome measure. We will not be able to do informative clinical trials of new treatment approaches without this.”

Dr. Jacobe and her colleagues are also creating educational materials for morphea patients, and parents of pediatric morphea patients, using information gathered from focus groups of patients living with morphea.

The physicians’ goal is to provide patients and caregivers with information relevant to their lived experience with morphea, so they have access to accurate and relevant information about the disease that will help eliminate unwarranted distress, and empower them to become successful self-advocates when needed.

Dr. Jacobe’s team are just completing a thorough revision, and she invites her colleagues to take advantage of these materials for their morphea patients. Once finished, they will be available on the Morphea Registry website, which also provides contact information for patients who would like to join the registry.

Suggested Reading

Abbas L, Joseph A, Kunzler E, Jacobe HT. “Morphea: Progress to date and the road ahead.” Ann Transl Med. 2021; 9:437–53.

Florez-Pollack S, Kunzler E, Jacobe HT. “Morphea: Current concepts.” Clin Dermatol. 2018; 36:475–86.

Zwischenberger BA, Jacobe HT. “A systematic review of morphea treatments and therapeutic algorithm.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011; 65:925–41.

Prasad S, Coias J, Chen HW, Jacobe H. “Utilizing UVA-1 phototherapy.” Dermatol Clin. 2020; 38:79–90.

Jacobe H. “Morphea (localized scleroderma) in adults: Management.” UpToDate. 2021.

Dr. Jacobe talks about the Dermatology Foundation’s role in her career in Profiles in Achievement.

Each year, the Dermatology Foundation carefully identifies emerging investigators whose ideas and proven ability to execute their promise to advance patient care.

In 2007 (Medical Dermatology CDA: Immunologic Profiles in Subsets of Morphea Patients) and in 2008 (Patient Directed Investigation Grant: Assessment in Morphea for the Establishment of Noncutaneous Disease [AMEND]), Dr. Jacobe was one of those young investigators. Her DF-supported success led to funding from the NIH and the Scleroderma Foundation, Gilliam Chair in Dermatology, UTSWMC Dean’s Scholar Program, UTSWMC Clinical and Translational Science Award, and KL2 Scholars Program.