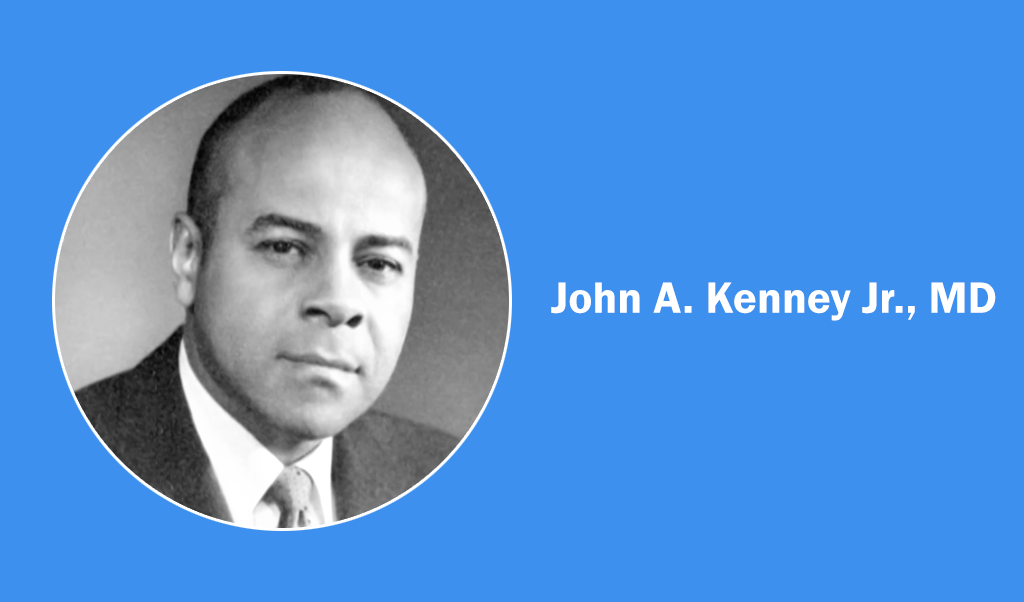

Dr. John A. Kenney Jr.

Photo courtesy of the Skin of Color Society

Against the backdrop of severe and persistent racism, including his family’s move to New Jersey in 1922 to escape threats from the Ku Klux Klan, Dr. John A. Kenney Jr. embarked on a journey that ultimately led his residents, mentees, and peers to honor him with the title, the Dean of Black Dermatology (Tuller 2003). Dr. Kenney, who was born in Tuskegee, Alabama, in 1914, expanded care for Black patients and opened doors for clinicians like him to practice the specialty. Over his 40-year career, he made monumental contributions to dermatology treatments in skin of color that continue to influence current generations of dermatologists. This was a man who had an outsized impact on his profession, his chosen specialty, and the people he mentored, as well as many he never met.

Among his accolades, Dr. Kenney was the first African American member of the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) and its first Black board member (1971–1973). He received the AAD’s Master Dermatologist Award in 1995 and its gold medal in 2001. At the time of his death, it was claimed he had mentored or trained one-third of all Black dermatologists practicing in the US (Washington Post 2003). He was the recipient of the Dermatology Foundation’s Clark W. Finnerud Award in 1988 for recognition of his mentoring efforts.

Rebat Halder, MD, Chair Emeritus of the Department of dermatology at the Howard University College of Medicine.

Dr. Kenney Jr. received his medical degree from Howard University in 1945 and completed his dermatology residency at the University of Michigan. He started a private practice in Cleveland and had a faculty position at Case Western Reserve University where he became one of the country’s first African American dermatologists. He returned to Howard in 1961 to become an assistant professor and taught at the university for nearly four decades. Dr. Kenney was president of the National Medical Association (NMA) (1962-1963), an organization his father co-founded because the AMA would not accept African American members. In 1963, he became chief of the dermatology division at Howard and, after what he called “a real fight and some politics,” he created a separate dermatology department and became its chair until 2001 (Bates College 1996).

The Dermatology Foundation awarded Dr. Kenney program development grants in 1967, 1970, and 1971, each focused on a specific aspect that enabled him to develop a dermatology department. Dr. Kenney continued practicing dermatology in Washington, DC, until the age of 85.

“We owe a debt of gratitude to Dr. Kenney for opening the eyes of the dermatology community to the problems and areas of investigation needed in skin of color,” said Rebat Halder, MD, Chair Emeritus, of the Department of dermatology at Howard University College of Medicine. “He was a true visionary who would be gratified to see what has developed in skin of color today. It’s an honor to have chaired the department he founded.”

Contributions to dermatology and beyond

Sewon Kang, MD, chair of the Department of dermatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“Dr. Kenney’s career and ideals have increased the diversity of those who practice dermatology,” said Sewon Kang, MD, chair of the Department of Dermatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “Our faculty and residents reflect this diversity and, in areas of dermatology where there’s a knowledge gap—especially in skin of color patients—we are actively trying to better understand these conditions. Diversity and inclusion are a core value of our institution.”

Following Dr. Kenney’s lead, Dr. Kang was one of the founding directors of the Skin of Color Society and created the ethnic skin program, including the establishment of the Ethnic Skin Dermatology Fellowship at Johns Hopkins. “This was a good opportunity for us to establish this research program and advance the field, but also care for our community members in inner-city Baltimore.”

Dr. Kenney strove to provide care for patients with skin of color and the diseases that affect them disproportionately, like vitiligo. At that time, Howard University was the main center for the treatment of vitiligo, particularly in skin of color. As a medical student there, Valerie Callender, MD, met Dr. Kenney in a clinic where she did vitiligo patient research.

Valerie Callender, MD, professor of dermatology at the College of Medicine at Howard, and medical director, Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center.

“I was in awe of Dr. Kenney,” said Dr. Callender, who is currently professor of dermatology at the College of Medicine at Howard. “He was dedicated to excellence and cared about everyone—patients, residents, students, and staff. He carried index cards in his pocket where he’d write personal comments about each patient, many who came from all over the world to see him. Even now, I see some of his patients who tell me how much they respected Dr. Kenney.”

Dr. Kenney instilled in his residents, including Dr. Callender, the importance of getting involved in professional organizations. “He told us, ‘You need to help make decisions for your specialty and for patients, and you have to have a seat at the table to do that,’” she said. “He encouraged us, not only to join, but to be active and aim for leadership positions.”

Dr. Callender, who is also the medical director of the Callender Dermatology & Cosmetic Center in Washington, DC, has been president of four dermatology organizations and, like Dr. Kenney, was the recipient of the DF Finnerud Award (2019).

Dr. Kenney’s influence on those he mentored

Dr. Halder was in his last year of medical school at Howard University in 1973 when he met Dr. Kenney. “He was a great influence on my decision to go into dermatology. I was impressed that Dr. Kenney was the only person in the country doing both clinical and laboratory studies on pigmentary disorders of the skin, particularly vitiligo and hyperpigmentation.”

Dr. Halder jumped at the chance to be a resident under Dr. Kenney’s tutelage. “I learned so much from him besides the science of dermatology,” he said. “His greatest influence on me was the way he interacted with medical students, residents, faculty, and patients, treating everyone with great respect and dignity.”

Dr. Halder, who was a founding member of the Skin of Color Society, credits the establishment of that organization as a way to promote the ideals of Dr. Kenney. “He was the first person in the United States to recognize we needed dermatologists who specialized in patients of color. He wanted our specialty to reflect that the majority of the world’s population is skin of color. He was more or less responsible for establishing what we now call ethnic dermatology.”

Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

“Dr. Kenney displayed remarkable resilience throughout his life and career,” said Amy J. McMichael, MD, professor of dermatology at Wake Forest School of Medicine in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. “He was resilient in getting his training, in going to unknown places, and in promoting the idea of ethnic skin so dermatologists would think about it. Dr. Kenney was someone who didn’t have an easy life, but he persevered.”

Obstacles still abound. In a specialty that deals with skin, the lack of racial and ethnic diversity among dermatologists is striking—only three percent of American dermatologists are Black (El-Kashlan et al, 2022). In addition, there is a lack of representations of skin of color in dermatology textbooks, and of those with skin of color in clinical trials and other research. “Belonging in dermatology, or not belonging, goes all the way back to John Kenney Jr., MD, Dr. McMichael said in her acceptance lecture when she received the John Kenney Jr., MD, Lifetime Achievement Award from the AAD in 2023 (McMichael 2023).

“Dr. Kenney’s many firsts as a Black dermatologist cleared the path for people like me to belong in a specialty we love and want to dedicate our lives to,” she said. “Because of who he was, I was able to become the first Black female dermatology chair in the country.”

References

Bates College. John Kenney ‘42 Lives the Sacred Oath. The Alumni Magazine. Summer 1996. https://abacus.bates.edu/pubs/mag/96-Summer/

El-Kashlan N, Alexis A. Disparities in Dermatology: A Reflection. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2022;15(11):27–29.

McMichael AJ. A question of belonging. DermWorld meeting news central. 2023 Mar 20. https://www.aadmeetingnews.org/aad-2023-annual-meeting/article/22766897/a-question-of-belonging

Tuller D. J. A. Kenney Jr., Medical Pioneer, Dies at 89. New York Times. 2003 Dec 6. https://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/06/business/j-a-kenney-jr-medical-pioneer-dies-at-89.html

Washington Post. John A. Kenney Jr., 89. Washington Post. 2003 Dec 6. https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2003/12/07/john-a-kenney-jr-89/b26bfa6c-5c46-4f31-9540-11cefb734352/