Serving the Underserved, Encouraging the Underrepresented

Hidradenitis Suppurativa in Skin of Color

January 2023

Dr. Ginette Okoye

Chair, Dermatology Howard University

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) was a skin disease Dr. Ginette Okoye had never given much thought to before she entered her first faculty appointment. “Actually, HS chose me,” she said. Her interest was piqued by Dr. Jerry Lazarus, Professor of Dermatology and Medicine at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, a man Dr. Okoye considers a mentor and with whom she shared clinic space. “Jerry is a giant in dermatology. I got to work with him at the tail end of his career, which was a blessing for me.”

She had just finished her dermatology residency at Yale, where she was chief resident, and was primarily interested in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Some of the patients Dr. Lazarus was seeing in the wound center at Bayview had both pyoderma gangrenosum and HS comorbidity. “He wanted me to consider HS because he found it interesting, the patients were underserved, and it affected people like me. He asked me to see one of his patients, a woman with HS. He said, ‘She’s the same age as you and the disease has destroyed her life. She could easily be your friend or your sister’.” Dr. Okoye saw the woman, who remains her patient to this day.

Dr. Okoye was drawn in by the horrible effects of the disease, how little was known about it, and the difficulty patients had finding care—few clinicians wanted to treat them because it was complicated and less satisfying than many other skin diseases with successful treatments. She saw more HS patients and, once word got out to other patients, and her colleagues realized that she had an interest in HS, she started getting plenty of referrals.

Along with the other skin disorders she was treating—scarring alopecia and cutaneous sarcoidosis among them—she learned that HS wasn’t the focus of significant research and that it struck a demographic that was historically underserved. Her experience also suggested that HS disproportionately affected those with skin of color. The academic dermatologists she shared her experience with suggested she was biased, and she wondered if they were right. As a Black doctor in Baltimore, was she attracting mostly Black patients or did her experience say something about the wider population? To answer the question, she needed to do some research, for which she had not been trained. She took a course in statistics, then accessed a large pool of patient data from Johns Hopkins to remove any potential bias. Her pioneering study—rejected multiple times before it was published—found that, indeed, HS was three times more prevalent among African Americans than Caucasians (Vlassova et al. 2015).

“I can’t tell you how difficult it was to get that paper published,” she said. “Some of the reviewer comments were scathing, rude, and discouraging.” Dr. Okoye understood what they were trying to say but felt this was something clinicians should be talking about. So she has continued the conversation in her research, her clinical work, and the leadership she provides as chair of the dermatology department at Howard University College of Medicine, a position she’s held for the past four years.

“I think my career is proof that it’s important to have a more diverse workforce, and greater diversity in the subject matter that interests researchers.”

Dr. Okoye’s research has confirmed the clear discrepancies for people with pigmented skin in terms of their access to treatment of HS, their participation in clinical trials (Okeke et al. 2022b) and other studies (Okeke et al. 2022c), and the paucity of images of Black and brown skin in dermatology publications and textbooks (Lester et al. 2020).

“We’ve started having those conversations, which is step one. I also think my career is proof that it’s important to have a more diverse workforce, and greater diversity in the subject matter that interests researchers. We need to open the doors of academic dermatology to people from different backgrounds and who have different perspectives.”

Genetic etiology

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic, recurrent, inflammatory skin disease characterized by lesions occurring in intertriginous and anogenital areas. It can progress to abscesses, fistulas, and scars. A decade ago, it remained unclear whether HS was an inflammatory disease or, since lesions ooze pus, infectious. Back then, Dr. Okoye and her colleagues used topical antibiotics like clindamycin as the treatment of choice. But, when she cultured pus derived from her patients’ HS lesions, she found a troubling trend of clindamycin-resistant S. aureus and S. epidermis infections. She co-authored a retrospective study looking at three antibiotics routinely used to treat HS and showed that patients taking any one antibiotic were more likely to have antibiotic-resistant cultures (Fischer et al. 2017).

“I didn’t realize the impact this would have on the literature,” she said. “Everyone was treating HS with antibiotics and then clinicians began considering anti-inflammatory treatments.”

HS is now known to be an inflammatory skin disease, and the only FDA-approved biologic treatment is Adalimumab, an immunosuppressive TNF-ɑ inhibitor.

Dr. Okoye’s research questions continued to evolve from her clinical experience. She saw an HS patient with a novel appearance. The patient’s sister and daughter had the same presentation. Autosomal dominant mutations in Ɣ-secretase genes had been identified in multiple families with HS (Pink et al. 2013), and Dr. Okoye wanted to know if there was a genetic explanation for this family’s disease. In collaboration with the Baylor-Hopkins Center for Mendelian Genomics at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, she found that four family members with HS had a heterozygous nonsense mutation while a fifth member, who did not have HS, did not have the mutation (Chen et al. 2015).

Disparities in the treatment of people with skin of color

“The main way these inequities affect patients is in terms of their ability to obtain their medication in a timely manner.”

There are many barriers to getting biologics used to treat any patient with HS. The drugs are expensive, require a prior authorization, which can take as long as a few weeks to obtain, and a clinician has to identify which specialty pharmacy that patient’s insurance company prefers.

It’s when the supplier has to connect with the patient that barriers specific to the types of patients Dr. Okoye sees are most troubling. The supplier won’t ship the medicine—on ice—until it contacts the patient. Her patients may struggle with economic housing insecurity or change phone numbers often, making it difficult to reach them. They may work nine-to-five at a job that makes it tricky to answer a phone or they live in challenging socio-economic conditions.

“When we looked at a 90-day period, 60% of our prior authorizations were for patients with Medicaid or Medicare,” she said. “Only 40% of those people got their medicine by the end of that 90-day period. How can we expect them to get better?”

- Dr. Okoye (left, leaning against the pillar) and her residents during the employee COVID vaccine rollout at Howard University.

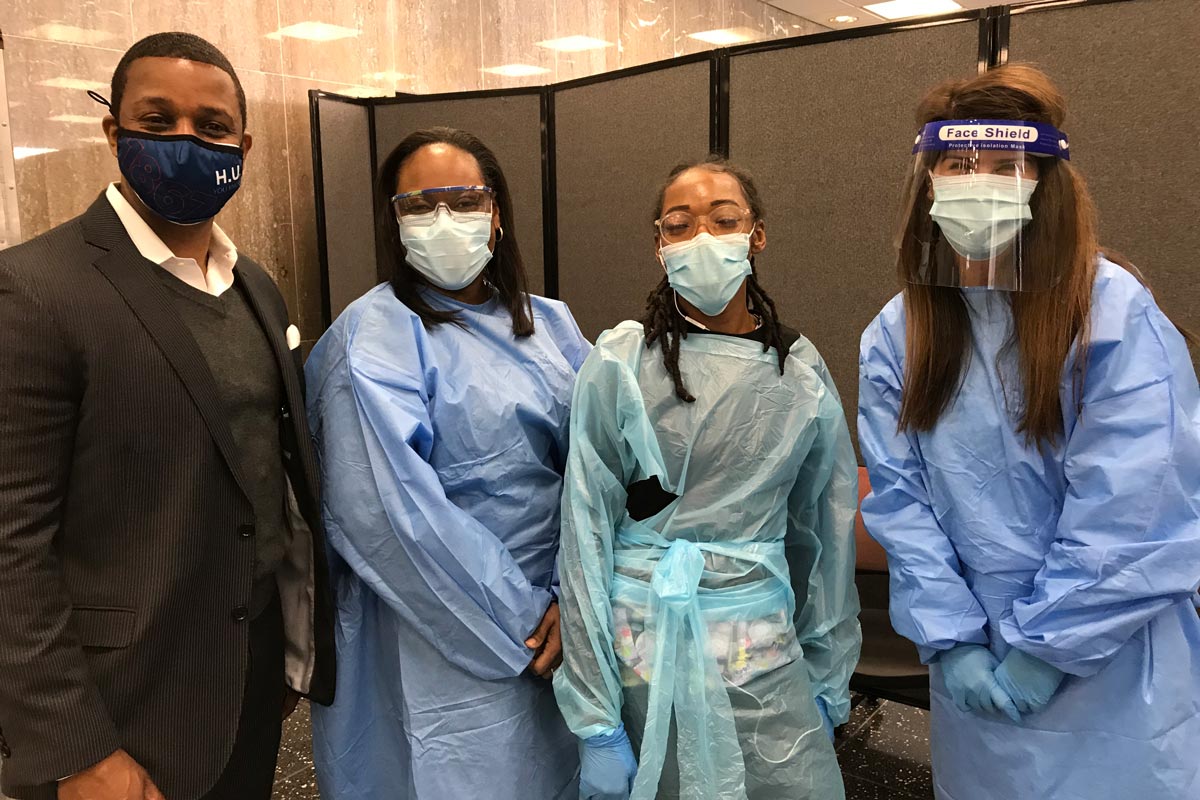

- (left to right) Michael Crawford, Associate Dean for strategy, outreach, and innovation, Howard University College of Medicine, Dr. Okoye, and staff members at the COVID vaccination clinic

COVID-19 made getting treatment worse

The discrepancies in treatment for both those with HS and COVID-19 became glaring during the pandemic. There is significant overlap of risk factors for both HS and severe COVID-19 (Seltzer et al. 2020), diseases that disproportionately strike Black and brown communities.

In the spring of 2020 with her clinic shut down, Dr. Okoye saw her community struggling with the pandemic. She led her dermatology residents and other clinicians to set up a COVID-19 testing facility in an underserved neighborhood with the highest rate of COVID-19 deaths in Washington, DC. For this community initiative, Dr. Okoye won a National Patient Care Hero Award from the AAD.

The rise of teledermatology

Dr. Okoye relied on teledermatology during the pandemic to monitor her HS patients. While it reduced the risk of progression, she found it was fraught with challenges. Not all her patients have a smartphone, an email address, or even adequate lighting in their homes.

“Our patients were mortified to send us photos of their genitals,” she said. “Not only was it difficult for them to take photos, but the quality of images also made it difficult to assess if their condition was improving.”

Other concerns included the difficulty establishing an emotional bond with patients, concerns about comfort and privacy, and an inability to palpate lesions. Dr. Okoye and her colleagues published potential solutions to these challenges (Okeke et al. 2022a) and encouraged dermatologists to review the AAD’s Teledermatology Toolkit.

“Telehealth can be useful in HS if you have the right setup, especially for the initial interview,” she said. “I take an extensive history during which patients often just need to talk about their condition and how it has destroyed their life. It’s also useful for a quick medication follow-up.”

A commitment to giving back

“I feel really fortunate as a Black person in America to have the resources I do. It’s important that someone who looks like these patients, and has been in their shoes to some extent, tries to make their experience better.”

During her childhood growing up in rural Trinidad both her parents, as well as her first professional mentor, her family’s country doctor, instilled in Dr. Okoye a commitment to giving back. “Dr. Sylvester had a huge impact on me just by showing up with his calm, gentle manner, and being so kind to our family. Sometimes he wouldn’t take any money. He really affected my ideas of what a doctor does. He was a Black man, so growing up it never occurred to me that I couldn’t be a physician. My doctor looked like me.”

“As dermatologists, we haven’t minded our reputation,” Dr. Okoye said. She is concerned some residents come to the discipline based on what they see on social media and don’t understand the full range of what medical dermatologists do. “We have lots of cosmetic dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons, but the people who see rashes and take Medicaid are few and far between, and almost all of us are clustered in cities.” She believes the solution is to attract people who have a passion for medicine—in particular, skin—and are willing to go where the need is greatest.

Out of this grew her desire to mentor and support those entering clinical and academic dermatology, particularly underrepresented minority women.

Supporting underrepresented minority women in academia

Dr. Ginette Okoye published four recommendations to support the challenges facing underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology (Okoye 2019). Since then, she has continued to implement these recommendations in her department.

1. Prioritize mentorship

To help others find a shorter path to success than hers has been, Dr. Okoye formed a group of young UIM [underrepresented in medicine] faculty that she meets with quarterly, as well as one-on-one as needed. “I show them how to get promoted, explain what is worthwhile to do in academics, and how to deal with the minority tax they’re probably paying.”

The Dermatology Foundation’s Diversity Research Supplement Award (DRSA) was developed in 2018 to enhance diversity in the field of dermatology and the specialty’s academic workforce. It’s a mentorship program in which eligible medical students select their mentors, who are former award recipients. Successful DRSA applicants belong to one or more groups considered to be underrepresented in biomedical research, in the completion of a defined full-time research plan.

Dr. Okoye points to the Academic Dermatology Leadership Program (ADLP) of the AAD as another step in the right direction.

2. Encourage professional development

She recommends students need to do well in medical school, get involved in research for at least one year, and publish.

3. Incentivize clinical care of the underserved

Underrepresented minority faculty are more likely to work in clinics in underserved settings, and those clinics are more likely to be chaotic, poorly run, and tend to be overbooked to account for ‘no shows’. “One of our clinics is in an underserved part of the city,” she said. “I’m adamant that it’s an attractive, bright, well-run space.”

Because her faculty usually bill Medicare or Medicaid, Dr. Okoye has negotiated salaries for potential future faculty, creating compensation packages that more closely align with what a good candidate might find in private practice where salaries are higher and often include a productivity bonus.

4. Legitimize diversity work and community service

The way she runs her department appears to be influencing the career decisions of her residents. Some of her recent and upcoming graduates are going into academia and reaching underserved parts of the country.

“When someone chooses to take Medicaid or go somewhere that’s underserved or wants to do research to contribute to a specialty, that’s huge. It’s gratifying that we’re making a difference with the residents.”

Future research for HS in skin of color

In addition to her work as a professor and chair of the department, Dr. Okoye serves on the research committee of the Skin of Color Society, is Associate Editor at JID Innovations, and is an editorial board member for the Journal of the National Association and the British Journal of Dermatology.

Together with her colleague, Dr. Angel Byrd, she is creating a unique repository of tissue and blood samples from Black and Hispanic HS patients for further research. The IRB process at Howard University was lengthy to protect this patient population. Dr. Okoye believes the transparency these requirements foster encourages patient enrolment.

“People often talk about the hesitancy of minority patients to participate in research,” Dr. Okoye noted. “But it’s been heartwarming to see how excited our patients are to participate. A few have declined, but most of them say, ‘Sign me up, what else do you need?’”

Between teaching, writing, seeing patients, and running the dermatology department, she finds she doesn’t have as much time for research as she’d like. “That was a really fun part of my career. But I’m finding it even more fun to help my faculty bring their projects to fruition, and they’re kind enough to include me. I feel like I put some bricks down on this road and now people can walk on those bricks and keep the road going. I can live with that.”

References

Chen S, Mattei P, You J, et al. γ-Secretase Mutation in an African American Family With Hidradenitis Suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(6):668–70. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/2119341Fischer AH, Haskin A, Okoye GA. Patterns of antimicrobial resistance in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(2):309–313. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(16)30615-6/fulltext

Lester JC, Jia JL, Zhang L, Okoye GA, Linos E. Absence of images of skin of colour in publications of COVID-19 skin manifestations. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(3):593–595. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/bjd.19258

Okeke CAV, Shipman WD, Perry JD, et al. Treating hidradenitis suppurativa during the COVID-19 pandemic: teledermatology exams of sensitive body areas. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022a;33(2):1163–1164.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09546634.2020.1781042

Okeke CAV, Perry JD, Simmonds FC, et al. Clinical trials and skin of color: The example of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2022b;238(1):180–184. https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/516467

Okeke CAV, Khanna R, Okoye GA, et al. Assessment of the generalizability of hidradenitis suppurativa microbiome studies: The minimal inclusion of racial and ethnic populations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022c;86(4):e159–e161. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(21)02726-2/fulltext

Okoye GA. Supporting underrepresented minority women in academic dermatology. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;6(1):57–60. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32025561/

Pink AE, Simpson MA, Desai N, et al. γ-Secretase mutations in hidradenitis suppurativa: new insights into disease pathogenesis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133(3):601–607.

Seltzer JA, Okeke CAV, Perry JD, et al. Exploring the risk of severe COVID-19 infection in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):e153–e154. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(20)30839-2/fulltext

Vlassova N, Kuhn D, Okoye GA. Hidradenitis suppurativa disproportionately affects African Americans: a single-center retrospective analysis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95(8):990–991. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26073615/