Creating Disease Severity and Quality-of-Life Scoring Systems for Blistering Diseases

Allow for outcome measurement in clinical trials to provide much-needed new treatments

March 2025

Dr. Dedee Murrell knows that patients with pemphigus and other blistering skin disorders can be deeply affected by their disease and the prolonged recovery process to regain a normal appearance.

Comparing the efficacy of existing therapies between clinical trials, as well as evaluating new treatments, requires an accurate and reliable assessment of the clinical nature of a disease. Yet the first comprehensive analysis of the interventions used to treat pemphigus, a range of autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBD), was inconclusive due to incomplete information, including absence of a uniform way of scoring patients in the limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) available at the time (Martin et al. 2009).

“Those trials were low quality and couldn’t be properly pooled because there were 256 different published definitions and outcome measures,” said Dedee Murrell, MD, PhD, DSc, the lead author of that Cochrane review. Dr. Murrell is Professor and Head of the Department of Dermatology, St. George Hospital, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. “The measurements we had at the time only led to a scale of mild, moderate, or severe symptoms, and the disease was measured differently from country to country.”

This study revealed a need for a validated clinical scoring system for pemphigus to facilitate clinical trials. Since then, Dr. Murrell and her colleagues have embarked on a mission to develop disease scoring systems for pemphigus and other blistering skin disorders.

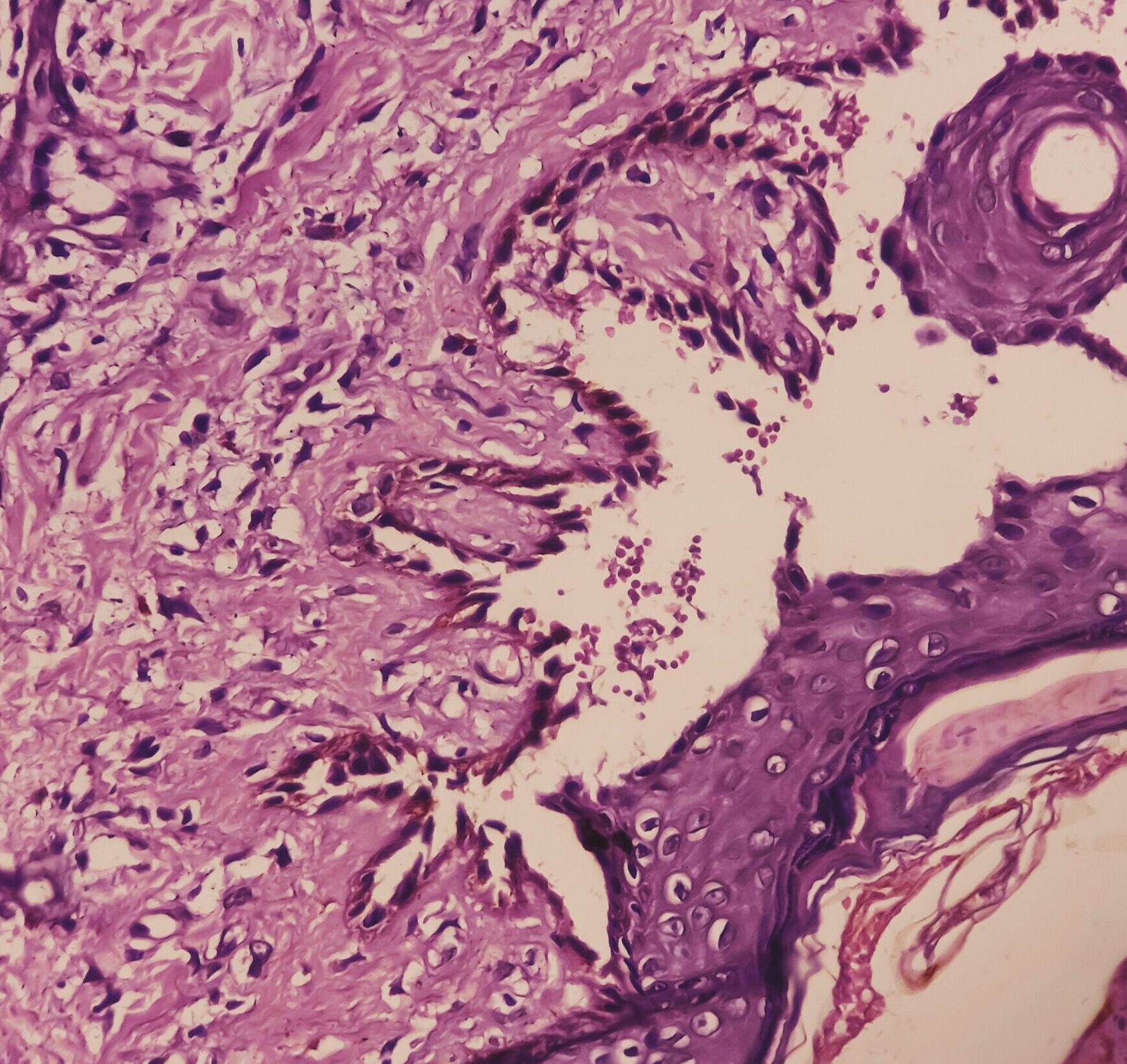

These debilitating diseases are characterized by painful, itchy, and sometimes bloody blisters on the face, hands, and elsewhere on the body. Bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulagris are AIBDs that result when autoantibodies target cells in the epithelial basement membrane zone. Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) is a rare genetic blistering disease, affecting people from birth. The same proteins that are attacked in adults with AIBD are missing or defective in newborns with EB. Children with EB have lesions in their eyes, nose, mouth, genitals, esophagus, as well as surface alterations. The psychosocial impact of pain, disfigurement, and stigmatization of inherited and AIBD can be significant (Jain and Murrell, 2018; White et al. 2024).

“These patients can develop PTSD,” said Dr. Murrell, who runs a lab focused on basic and translational research in blistering diseases. “Patients can be deeply affected by their disease and the prolonged recovery process to regain a normal appearance, leaving them anxious about a recurrence.”

Conventional treatment includes topical and oral corticosteroids to reduce inflammation, and antibiotics to treat infections and potential sepsis. With prednisone, the level of autoantibodies causing skin blistering is lowered but, if a patient weans off steroids, they are likely to experience a recurrence of the disease. People suffering from inherited and autoimmune blistering diseases are desperate for better treatments; biologics—monoclonal antibodies and JAK inhibitors—are newer, promising treatments that last longer. For example, after treatment with rituximab, a monoclonal antibody that destroys CD20+ B and pre-B cells, the autoantibodies causing blistering are suppressed for six to 12 months before reemerging.

These debilitating diseases are characterized by painful, itchy, and sometimes bloody blisters on the face, hands, and elsewhere on the body.

After completing the Cochrane review in 2009, Dr. Murrell and her colleague Victoria Werth, MD at the University of Pennsylvania met with clinicians to discuss how to develop an accurate and reliable disease index for pemphigus. They met at conferences in Paris, Japan, and the US to come to an agreement about how to score the disease using photographs.

“Our challenge was to develop a scoring system that was simple enough for doctors to perform, yet reliable enough to yield a similar score whether a clinician was in Sydney or Japan,” Dr. Murrell said.

It took nearly three years for them to create and test the Pemphigus Disease Area Index (PDAI) and test performance with these scores in a clinical study (Rosenbach et al. 2009). The study included 10 dermatologists and 15 pemphigus patients. It compared the PDAI to another recent scoring system, the Autoimmune Bullous Skin Disorder Intensity Score (ABSIS), as well as the Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA). The study validated the PDAI as a scoring system with good intra-rater and inter-rater reliability and the benefit of being rapidly completed by clinicians in less than three minutes. They concluded that the PDAI could be used in clinical trials for pemphigus. Dr. Murrell, Dr. Werth and the International Blistering Diseases Consensus Group (IBDG) then set about creating the Bullous Pemphigoid Disease Area Index (BPDAI) for use as an outcome measure in RCTs of bullous pemphigoid (Murrell et al. 2012). Her research also validated BPDAI for use in clinical studies (Wijayanti et al. 2017).

“Our challenge was to develop a scoring system that was simple enough for doctors to perform, yet reliable enough to yield a similar score whether a clinician was in Sydney or Japan.”

Dr. Murrell created a separate scoring system for epidermolysis bullosa (EB), the Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI) (Loh et al. 2014). EBDASI is more complicated than the other disease indices because children with EB have involvement in multiple tissues, including the skin, mucosae, esophagus, stomach, kidneys, ureters, bladder, urethra, and lungs. EBDASI has been used in clinical trials, including for a topical gene therapy, Vyjuvek (beremagene geperpavec-svdt), an FDA-approved therapy that delivers normal copies of a mutated gene to damaged skin (Khan et al. 2023) and for Filsuvez, a topical gel containing an extract from birch bark (Kern et al. 2023). Dr. Murrell was involved with clinical studies for both new drugs.

Professor Murrell completed her medical training at Cambridge and Oxford Universities. Following three years in internal medicine in the UK and US, she pursued dermatology training at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. She had fellowships in dermatopharmacology at Duke University and cell biology at New York University. Dr. Murrell became a clinical scholar in psoriasis and EB at Rockefeller University in the lab of Jim Krueger, MD, PhD. She completed her doctorate on the pathogenesis of blistering disorders at the University of New South Wales in 2006. She was the first Australian to receive the Medical Dermatology Society Lifetime Achievement Award (2024).

Dr. Murrell began doing clinical trials in cardiology in England, then in dermatology at Duke University. She has been an investigator/advisor for clinical trials of treatments for blistering diseases conducted by AstraZeneca, GSK, Lilly, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, Regeron, Argenx, and other pharmaceutical companies.

She prefers to be brought onto a new study early because her extensive experience in clinical trial design allows her to avoid common mistakes, such as not including placebo controls. This experience was instrumental in revealing the inefficacy of an injected cell therapy for EB that had previously shown positive treatment outcomes—in a study lacking placebo controls (Wagner et al. 2010). When Dr. Murrell conducted the first placebo-controlled RCT for the injected allogeneic cell therapy, she found that a placebo had the same positive effect as the injected cells (Venugopal et al. 2013). The authors hypothesized that injection of the placebo might have led to the synthesis of collagen at the site of injection, mimicking debridement that can trigger wound healing.

Developing quality of life scores for use in clinical trials

While the FDA tends to focus on the objective improvement of a disease score, treatments must also improve a patient’s quality of life (QoL). More and more, QoL scores are a secondary outcome measure included in clinical trial design. To this end, Dr. Murrell and her colleagues created the first QoL scoring system for AIBD, called the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (ABQOL) questionnaire (Sebaratnam et al. 2013). This 17-question, self-reported questionnaire is more sensitive in discriminant validity, and of similar quality in convergent validity, to other available tools (Sebaratnam et al. 2015).

Dr. Murrell is currently involved in a trial for Dupixent (dupilumab) for the treatment of bullous pemphigoid. Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, cytokines believed to be involved in atopic dermatitis. The RCT uses the BPDAI to assess clinical severity and ABQOL to assess quality of life. These scores have also been used to establish cutoffs to assess disease severity as mild, moderate, or severe. This is useful as drugs—especially expensive ones—are sometimes only approved for patients who have moderate-to-severe disease.

The value of differentiating disease QoL from treatment QoL

Dr. Murrell was also instrumental in pioneering the need to differentiate a blistering disease patient’s QoL related to their disease progression from another assessment rating the effects of ongoing treatments.

”It’s important that conventional corticosteroid and antibiotic treatment relieve blistering and improve a patient’s quality of life,” Dr. Murrell said. “But at what cost? The treatments are ongoing, doctor visits continue, and blood tests are routine. So, while disease QoL may improve, the effects of the treatment often remain—and can be onerous.”

What she identified was a need for a secondary QoL measurement related to treatment—frequency of blood tests, the need for special clothing, the development of skin thinning, and complications related to the treatment. Dr. Murrell created the Treatment of Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life (TABQOL) questionnaire (Tjokrowidjaja et al. 2013) to separate as assessment of the effects of treatment from a disease QoL questionnaire like ABQOL.

“We realized a quality-of-life assessment can’t contain questions about both the change in disease symptoms and the effects of treatment,” Dr. Murrell said. “If it contains both, you end up masking the treatment benefits related to the disease.”

“These scoring systems we’ve created provide a toolbox of outcome measures that clinicians and companies can use to design clinical trials to test whether new drugs are efficacious.”

For example, a patient might be annoyed to have to go to a blood lab every two weeks yet pleased that their blisters have disappeared. The total score might not change because one part of it would get better as the disease disappeared as the other one got worse as the treatments continued. Dr. Murrell has also created the Quality of Life in Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB-QOL) (Frew et al. 2009).

“These newer biologic medications are extremely safe and very convenient,” Dr. Murrell said. “A patient can have a subcutaneous injection every few weeks and more or less forget about their disease, instead of needing to take tablets twice a day, every day.”

Although the studies are not yet complete, she anticipates that some of the biologic treatments coming out will have a positive effect on the burden of treatment because they require fewer blood tests and have fewer side effects.

“I love when we can develop better treatments for patients than what currently exists,” Dr. Murrell said. “These scoring systems we’ve created provide a toolbox of outcome measures that clinicians and companies can use to design clinical trials to test whether new drugs are efficacious.”

References

Ferries L, Gillibert A, Duvert-Lehembre S, et al. Sensitivity to change and correlation between the autoimmune bullous disease quality-of-life questionnaires ABQOL and TABQOL, and objective severity scores. Brit J Dermatol. 2020;183:944–945. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bjd.19173

Frew J, Martin L, Nijsten T, Murrell D. Quality of life evaluation in epidermolysis bullosa (EB) through the development of the QOLEB questionnaire: An EB-specific quality of life instrument. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(6):1323–1330.

Jain SV, Murrell DF. Psychosocial impact of inherited and autoimmune blistering diseases. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2018;4:49–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2017.11.004

Kern JS, Sprecher E, Fernandez MF, et al. Efficacy and safety of Oleogel-S10 (birch triterpenes) for epidermolysis bullosa: results from the phase III randomized double-blind phase of the EASE study. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188(1):12–21. https://academic.oup.com/bjd/article/188/1/12/6763699?login=false

Khan A, Riaz R, Ashraf S, et al. Revolutionary breakthrough: FDA approves Vyjuvek, the first topical gene therapy for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023;85(12):6298–6301.

Loh CC, Kim J, Su JC, Daniel BS, et al. Development, reliability, and validity of a novel Epidermolysis Bullosa Disease Activity and Scarring Index (EBDASI). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(1):89–97.e1-13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.09.041.

Martin LK, Werth V, Villanueva E, et al. Interventions for pemphigus vulgaris and pemphigus foliaceus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006263.

Murrell DF, Daniel BS, Joly P, et al. Definitions and outcome measures for bullous pemphigoid: recommendations by an international panel of experts. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(3):479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.06.032.

Rosenbach M, Murrell DF, Bystryn JC, et al. Reliability and convergent validity of two outcome instruments for pemphigus. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(10):2404–2410. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.72. https://www.jidonline.org/article/S0022-202X(15)34089-6/fulltext

Sebaratnam DF, Hanna AM, Chee SN, et al. Development of a quality-of-life instrument for autoimmune bullous disease: the Autoimmune Bullous Disease Quality of Life questionnaire. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(10):1186–1191. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamadermatology/fullarticle/1724034?appId=scweb

Sebaratnam DF, Okawa J, Payne A, et al. Reliability of the autoimmune bullous disease quality of life (ABQOL) questionnaire in the USA. Qual Life Res. 2015;24(9):2257–2260.

Stone C, Bak G, Oh D, et al. Environmental triggers of pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid: a case control study. Front Med. 2024;11. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1441369

Tjokrowidjaja A, Daniel BS, Frew JW, et al. The development and validation of the treatment of autoimmune bullous disease quality of life questionnaire, a tool to measure the quality-of-life impacts of treatments used in patients with autoimmune blistering disease. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:1000–1006.

Venugopal SS, Yan W, Frew JW, et al. A phase II randomized vehicle-controlled trial of intradermal allogeneic fibroblasts for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6):898–908.e7.

Wagner JE, Ishida-Yamamoto A, McGrath JA, et al. Bone marrow transplantation for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:629–639.

Werth VP, Murrell DF, Joly P, et al. Bullous pemphigoid burden of disease, management and unmet therapeutic needs. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024a. doi: 10.1111/jdv.20313. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.20313

Werth VP, Murrell DF, Joly P, et al. Pathophysiology of Bullous Pemphigoid: Role of Type 2 Inflammation and Emerging Treatment Strategies (Narrative Review). Adv Ther. 2024b;41:4418– 4432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12325-024-02992-w

White MA, Hoffman VM, Yale M, et al. Psychosocial burden of autoimmune blistering diseases: A comprehensive survey study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024.doi: 10.1111/jdv.20156. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jdv.20156

Wijayanti A, Zhao CY, Boettiger D, et al. The reliability, validity and responsiveness of two disease scores (BPDAI and ABSIS) for bullous pemphigoid: Which one to use? Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 2017;97:24–31.