Through the Lens of Education

Timothy T. Berger, MD, 2023 DF Lifetime Career Educator Award

March 2024

Timothy T. Berger, MD, is the recipient of a DF Lifetime Career Educator Award.

Timothy T. Berger, MD, has always been a visual person and likes the stories art can tell. He understands something in the clinic better when he can draw a picture of it. Dr. Berger was Professor of Clinical Dermatology in the Department of Dermatology at the UCSF School of Medicine and, for his dedication to education and mentorship, is the recipient of a Lifetime Career Educator Award.

DF Lifetime Career Educator Award: What it Takes

The Lifetime Career Educator Award honors a full-time academician who has dedicated their career to educating dermatology residents and fellows. They have a lifelong history of dedicated service as a mentor and role model for trainees in the department. The candidate should be known for their ability to enthusiastically impart knowledge, as well as inspire the student of dermatology to pursue a greater understanding of the specialty.

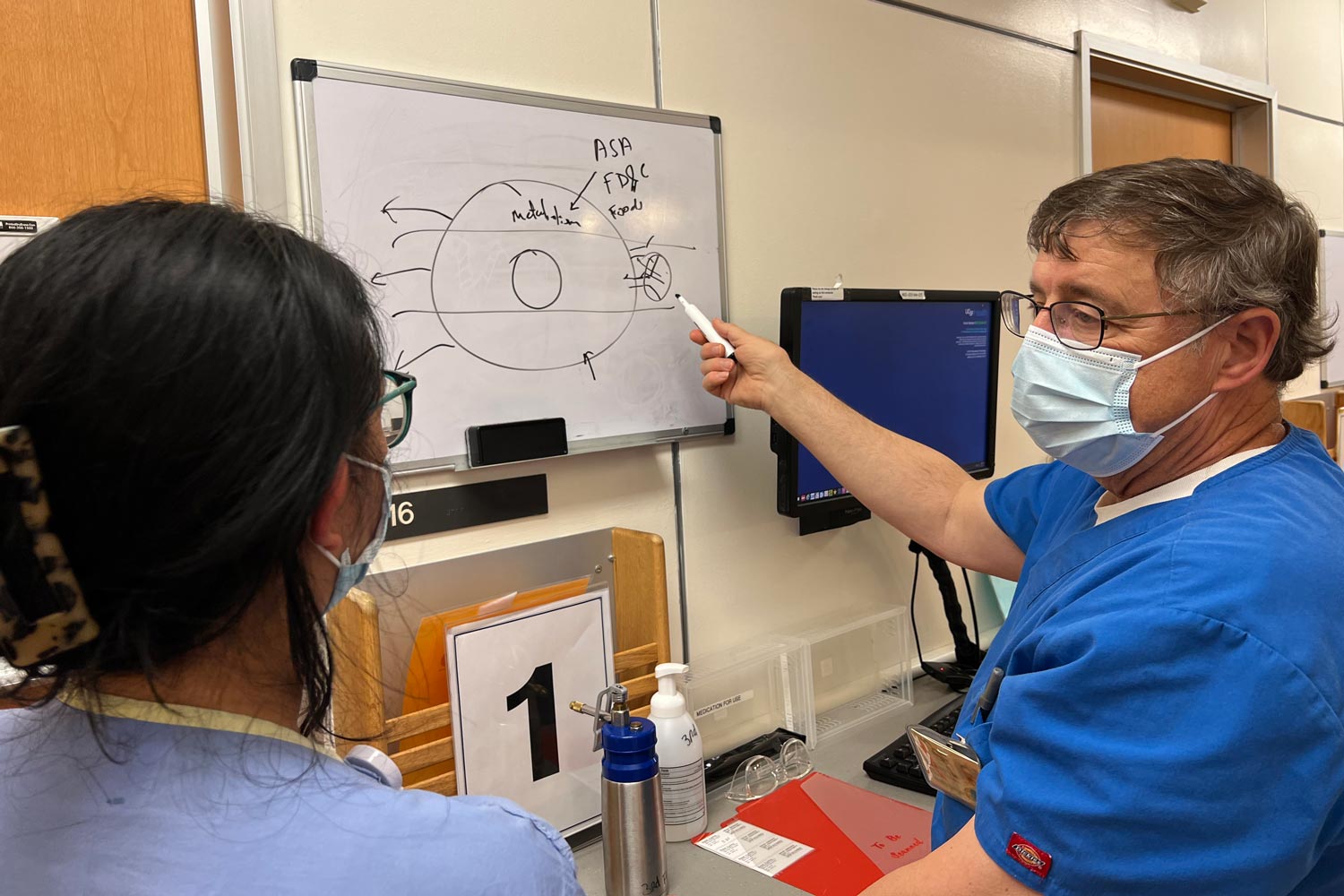

He carries a marker with him when he’s teaching in one of the numerous clinics at UCSF, using it to draw stories on whiteboards to help illustrate a point. His residents often photograph these drawings and file them to refer to later. He uses this visual storytelling as a way to communicate, knowing the people he teaches are also visual learners.

“Dermatology is the skin telling its story,” he said. “We just have to understand how to read that story. Our patients actually know what they have when they come to the clinic but, because they haven’t been to medical school, they can’t explain it. Our job is to translate their story into the medicine we know. Then we can apply treatment to help them get better.”

“It’s a great honor to be recognized by the Dermatology Foundation, which is a huge supporter of research education,” he said. “I’m also honored to be the recipient of this award because I’ve had the pleasure of being mentored by some of the previous award winners, including Dr. Vera Price who was in our department.”

Becoming an educator

Dr. Berger was drawn to dermatology while he was a medical student at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School. Although he was torn between pathology and dermatology, he was able to satisfy both his passions by completing his internship and residency in dermatology, after which he had a fellowship in dermatopathology.

“I figured I could either look at the skin and read the story it was telling, or I could use pathology data to determine the basis of disease and try to make the story up. Now I use both of these approaches to treat patients.”

His clinical journey began when he was hired to work at San Francisco General Hospital, partly on the strength of his Army experience seeing patients with sexually transmitted infections. It was a fraught time in San Francisco, with a chancroid syphilis epidemic coinciding with the AIDS epidemic.

During his decade at the hospital, he became interested in taking on formal education and became the residency program director, which he did for another ten years. When his mentor retired, Dr. Richard Odum, Dr. Berger became the senior clinical dermatologist for Northern California.

“At the time, there were no treatments for HIV disease,” he said. “Patients were often told, ‘We can’t help you. HIV disease is causing your skin problems, and we can’t fix it.’ Patients became desperate and felt unwelcome by the specialty.”

He credits the educational sessions at the DF Clinical Symposium with generating a cadre of dermatologists who were willing to step up and manage these patients.

Fortunately, there was a sea change as newer interns, who had seen many patients with HIV, began calling Dr. Berger for advice on how to best manage their patients’ condition. He credits the educational sessions at the DF Clinical Symposium with generating a cadre of dermatologists who were willing to step up and manage these patients.

Currently, Dr. Berger is an attending physician four half-days per week. He supervises residents and medical students in the clinics. He recently retired and is working part time, continuing to teach and do some limited research.

Telling the patient’s story

Dr. Berger regularly teaches medical students, dermatology residents in clinics and formal lecture settings, and at regional, national and international conferences. With a colleague, he co-created a curriculum for internal medicine and primary care residents, as well as an online, open access curriculum for medical students in dermatology. He co-authored Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin (11th edition). Dr. Berger has mentored most of the clinically based junior faculty currently on the department’s staff, and acts as an advisor to the senior faculty.

He instills in young students to learn by observation and to practice communicating with everybody whether they are a Nobel Prize winner—there have been a few come through the clinics in which he’s worked—to someone new to the United States who may not understand the clinic’s approach to medicine.

With a colleague, he co-created a curriculum for internal medicine and primary care residents, as well as an online, open access curriculum for medical students in dermatology.

“As an educator, I’ve learned how to navigate between the needs of the learner and those of the patient. The patient is telling a huge story, with lots of questions and information. Yet, for the learner, each patient has one important piece of knowledge. What is the one thing that this patient illustrates best? Is it the appearance of their skin lesion? Or perhaps they began itching this week and may have scabies. I can’t teach everything from one patient, but if every time a learner sees a patient, they learn one thing, they’ll have learned 10,000 things by the time they finish their training.”

Following a survey of medical students, house staff, academic physicians, and primary care doctors about the state of dermatology instruction in the US, Dr. Berger recommended a standardized dermatology curriculum for all medical students in the country, a position accepted by the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD). He currently chairs a working group of the AAD to oversee curriculum design.

Building an engaging atmosphere

Dr. B—as he is known to residents and medical students—strives to be the best role model he can be and to engage learners in the educational opportunity each patient encounter provides. He believes medicine should be exciting and engaging and hopes the curiosity residents have in the beginning is still there when they leave three years later to practice dermatology on their own.

“I want the joy they get from helping patients to still be there. I like to emphasize that, since they’ll be in this specialty for 40 years, they need to do it in a way that’s going to keep them happy.”

The focus of future research

Dr. Berger continues to initiate new areas of research, one of which is to enhance the understanding of the basis of itch. “One of the advantages of being an academic is that I can change what I do,” he said. “Basically, whatever comes through the clinic door is what I’m going to be interested in. Currently, what is coming through those doors are older patients who have terrible itching that is ruining their lives.”

“We’re trying to do the same thing with itching that we did with HIV disease, to develop enough science and understanding that physicians in the community will dig in and try to help.”

Starting in 2007, he combined his understanding of the immunological and cutaneous consequences of aging with the range of pruritic eruptions he saw among older adults in the clinic. From this he developed a classification scheme for clinicians. This work has been summarized in two recent chapters in the textbooks, Neurology and General Medicine and Dermatology Clinics.

“We’re trying to do the same thing with itching that we did with HIV disease, to develop enough science and understanding that physicians in the community will dig in and try to help. Patients often tell us the story of how they’ve suffered, either because their disease wasn’t fully understood, or people didn’t listen. That compels us to go back to our clinical colleagues and tell them, ‘No, you really can help these people.’ I want to be the broker between these patients and their dermatologists.”

There are gaps, however, where dermatologists are unable to make that transition—the patients tell their stories, but the science is unable to provide the answer for why it’s happening.

“While our specialty focuses on classic dermatologic diseases—psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, prurigo nodularis, vitiligo, and alopecia areata—there are many diseases that science has left behind,” said Dr. Berger. “These are areas where there’s opportunity for science to progress.”

In addition to itch disorders, hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a skin disease that clinicians struggle to treat, and young scientists see as a research opportunity.

He also wants to see more and better collaboration between dermatology and other specialties. To this end, his department has established a joint clinic, including neurologists who see patients with sensory disorders, rheumatologists, and plastic surgeons who see patients with HS. He believes these connections are important and have led to increased understanding of dermatology within the scientific and clinical communities.

“Someone from the NIH once told me it tends to fund grant applications for which the technology is available to answer the question being asked,” he said. “The Foundation’s way of creating awards has been so effective because, not only does it support orphan diseases that need special attention, but they also pick those topics that are doable and allow the investigator to succeed. It’s also where mentorship plays a key role. There have been multiple generations of physician-scientists funded by the Foundation. Now, senior scientists can help junior scientists create the kinds of applications that are going to be successful.”

Dr. Berger carries a marker with him when he’s teaching and uses it to draw stories on whiteboards to help illustrate a point. He uses this visual storytelling to communicate, knowing the people he teaches are also visual learners.

Role with the Dermatology Foundation

“I’m so grateful to the Dermatology Foundation,” said Dr. Berger. “Without it the science of dermatology wouldn’t be as advanced as it is, and we wouldn’t have people being as interested in the science. There’s always been a need to bridge the time between when a resident finishes their training until they can obtain funding at a more stable level through the NIH or some other mechanism. The Foundation was able to bridge that gap for many of our physician-scientists who are now faculty members. I saw the results of this effort and that motivated me to stay involved with the Foundation.”

He hopes the specialty will find ways to take advantage of the support offered by the Foundation that allows physician-scientists to develop innovative drugs that will benefit patients. Dr. Berger noted that, while the specialty of dermatology and the number of physician-scientists in dermatology has grown since he started 50 years ago, the Foundation has kept up with the demand and continued its support of young investigators.

“I’m so grateful to the Dermatology Foundation. Without it the science of dermatology wouldn’t be as advanced as it is, and we wouldn’t have people being as interested in the science.

“Kudos to the leadership of the Foundation for connecting young scientists with private practitioners,” he said. “Those in private practice are able to see that the drugs to help their patients will come from the discoveries of these young scientists. “It just has to happen faster than it is at the current pace. We’re going to need bigger grants and awards so these young scientists can survive.”

And, while his story is far from told, the career of Dr. Berger has exemplified what he considers the two goals of any academic—to advance the field and to train the next generation.

“I set out to be a mentor, a teacher, and an excellent clinical dermatologist so I could help my patients. It’s really gratifying to receive this award from the Foundation and humbling to have the specialty recognize my efforts. This makes me feel like, OK, I did what I set out to do.”

Learn more about the DF Honorary Awards.

Biography

Dr. Timothy Berger is a dermatologist who specializes in rare, challenging and complex skin disorders. He cares for patients with autoimmune bullous disease, viral skin diseases, sexually transmitted diseases of the skin, tropical skin diseases, photosensitivity disorders, infectious diseases of the skin, warts and pruritus.

He was inducted into the UCSF Academy of Medical Educators, an honor bestowed on faculty members who have shown dedication to medical student teaching. In 1989, he was honored with the Henry J. Kaiser Award for Excellence in Teaching. In both 1991 and 2001, the UCSF residents in dermatology named him teacher of the year.

Publications

Gutierrez RA, Berger TG, Shah V, Agnihothri R, Demir-Deviren S, Fassett MS.Evaluation of Gabapentin and Transforaminal Corticosteroid Injections for Brachioradial Pruritus. JAMA Dermatol. 2022 Sep 1;158(9):1070-1071.

Linos E, Berger T, Chren MM. In reply: Counterpoint: Limited life expectancy, basal cell carcinoma, health care today, and unintended consequences. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022 May;86(5):e203.

Rahbar Z, Cohen JN, McCalmont TH, LeBoit PE, Connolly MK, Berger T, Pincus LB. Cicatricial Pemphigoid Brunsting-Perry Variant Masquerading as Neutrophil-Medicated Cicatricial Alopecia. J Cutan Pathol. 2021 Nov 29. Online ahead of print.